Over my nearly 30 years of work, I’ve picked up a bunch of theories and models along my way. Some of them are useful, many of them I’ve forgotten. One that I keep coming back to is the 7-S Model.

Developed by Tom Peters and Robert Waterman in the 1980s whilst they both worked at McKinsey, 7-S is a helpful mnemonic to understand the way in which an organisation works (or doesn’t). It also fulfils my personal rule that a useful model is expressed in 12 boxes or fewer. That’s a personal rule that I also know I break on occasion.

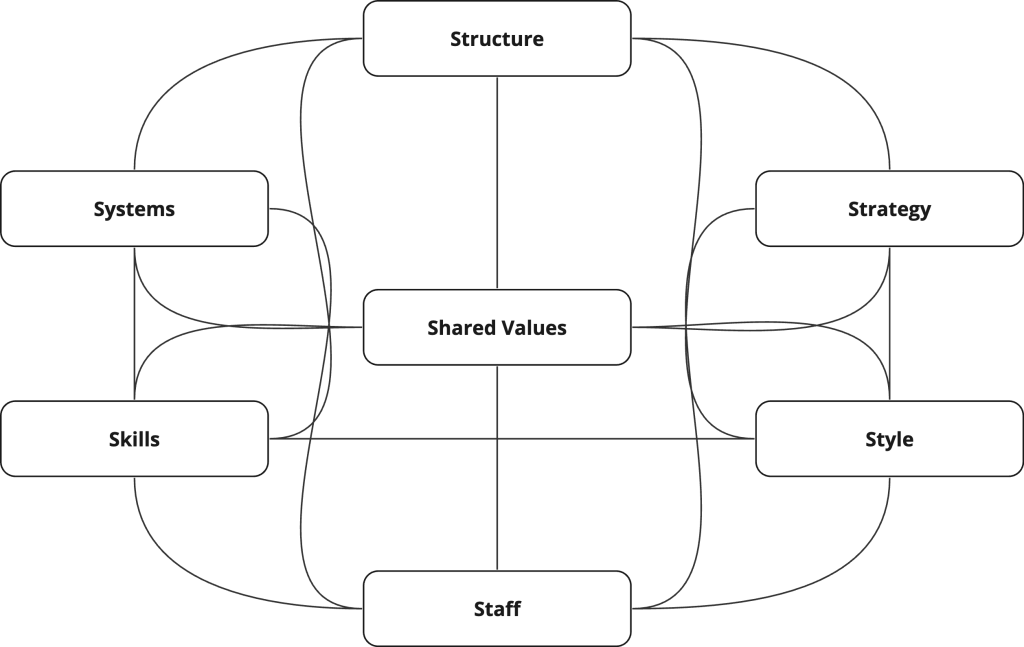

What 7-S does is describe seven dimensions of an organisation, and the theory is that all need to be acting in harmony for an organisation to perform well. They also open up seven lines of investigation regarding the things that a business might consider when planning for change.

The model – three “hard” factors

The first three dimensions are often referred to as the Hard Ss.

Systems refer to technology systems, processes, frameworks and similar tools that define the way in which work activities are carried out.

Structure is the (often hierarchical) way in which people in an organisation are organised, often represented in the form of Organograms.

Strategy is the stated way in which the organisation intends to act in response to the world around it.

Three “soft” factors

The next three dimensions are often referred to as the Soft Ss and are more focused on the people in an organisation.

Skills refers to the capabilities and knowledge of the people within the organisation.

Staff are the people themselves.

Style is how groups, and in particular management, behave in their approach to management and leadership.

Values to link it all

At the centre of the model is the concept of Shared Values – the culture of an organisation that is held in common by people across the business. Or not, as the case may be.

Technology focuses on the hard Ss

As a generalisation, my experience has found that most technology teams focus on the Hard Ss, and Systems in particular when it comes to attempting to make changes happen.

The introduction of new Systems in isolation, whether software (“Let’s use Jira!”) or more process-centric (“Let’s use Agile!”) is too often seen as the answer to a problem of performance or throughput or whatever else. How technology teams introduce such change are reminiscent of the old Spanish proverb the cobbler’s child has no shoes.

Occasionally technology teams will look at Structure either from a whole-team re-organisation or at a micro level through how teams themselves are structured as a result of the introduction of a new approach in something like development methodology.

Technology Strategies may come and go but need to align with the broader organisational strategy. The number of organisations that operate either without or despite a strategy is something I don’t think gets nearly enough coverage.

It’s harder in the soft Ss

When it comes to the softer Ss, technology teams struggle somewhat more.

There have been skills and capabilities frameworks in place now for decades – I was using SFIA back in my BBC days, and these days the UK Government DDAT Job Families is another really valuable resource.

But so often I see technology teams making technology platform decisions, whether at a local or organisational level, that pay too little attention to the skills that will be required to actually use those platforms. Sure, go for the latest and greatest language/platform/hype, but only when you have checked that not only can you afford the skills that will be required, but also that you’ll be able to attract the people with those skills to your organisation.

We now live in a very different employment market than before the pandemic, and although the market is hard at the moment if you want to attract and retain the right staff you need to understand the national and even global market in which technology skills now operate. What is the value proposition that you offer to people? If it’s not above and beyond merely pay and benefits, you might struggle to get the people you need – it’s a competitive market.

The style of management and leadership in a technology organisation is also crucial to delivering meaningful change. In particular, overly directive styles will stymie attempts to introduce agile methods which, by their nature, are fluid frameworks that rely on giving people autonomy to get on with their work.

Fostering that style of working in a hierarchical organisation is possible if the leadership of the technology group really put their mind to it, but often one ends up becoming something of a human shield and protecting teams from the overriding culture is exhausting. I speak from experience.

So what are your values?

Corporate values exercises became very fashionable in the 1990s and 2000s, and most businesses of any scale these days will have a ragtag list of adjectives and verbs that are flashed in front of new joiners during induction phases. These word salads were often imposed on organisations, no doubt many as a result of things like the 7-S model.

Within a technology team, though, what really are the values that are held by individuals in the group? Are they aligned with the rest of the team? Are they in harmony with the greater organisation? Does everyone agree? Have you ever had this conversation at scale?

Too often it’s assumed that everyone is aligned. That’s a very risky assumption to make if it hasn’t been and continues to be regularly tested.

Is it just tech teams?

I’ve focused here on technology teams and misalignment or unawareness of the 7-Ss because that’s been my primary field of vision professionally since 1993. I’m sure other functions are better. I’m equally sure most are just as bad.

But just because everyone else is crap at it, doesn’t mean technologists shouldn’t strive to be better. Particularly because we are often seen as agents of change within our organisations, yet can be pretty poor at doing it ourselves.

So what?

Change is hard. But it’s also perfectly possible.

The experience of the lockdowns showed that people can adopt new ways of working at pace. However, if it takes a global pandemic to introduce change successfully we are in trouble.

I’m also certainly not arguing that you have to plan for every single one of the Ss to be factored into change planning. We can’t plan everything perfectly upfront – surely that’s the biggest learning of thirty years of the adoption of iterative agile methods in software delivery?

But one-dimensional approaches to change are destined to disappoint. Just sticking in Jira, or just adopting SCRUM are unlikely to yield results if you don’t take a more holistic view. And that’s what 7-S can start to apply – a 7-box lens through which to view the changes you might need to make.

One thought on “7-Ss for Technology teams”