One of the models that’s had the most impact on me in the last 10 years is from a book called Collaboration by business academic Morten Hansen.

The model he describes outlines 4 systemic barriers that exist within organisations to us being able to collaborate effectively. They look like this:

The “not invented here” barrier is when people resist collaboration with others because they believe that they should do something on their own. That might be because they believe that they can do it better than others (I’ve seen this a lot in self-described technology companies who think that building their own CRM or ERP is a good idea).

It might be because they think that working with others is somehow an admission of professional failure. In the West, and in the US and the UK in particular, the cult of the individual makes us often feel that we need to take everything on ourselves.

The hoarding barrier is when people don’t want to collaborate with others because they somehow believe it will diminish their professional or political standing. Knowledge is power, and all that jazz.

The search barrier is when people are simply unable to find people with whom they might work. Corporate knowledge is usually in people’s heads, but the mechanisms to find them are usually based around where they sit (org structure) rather than what they know (because it’s in their heads).

Finally, the transfer barrier stops people from working with one another because they simple don’t have common language to be able to do so. My now oft-cited example is of three months of my personal confusion working in the housing sector, hearing the word “developers” and thinking about people cutting code, not people laying bricks.

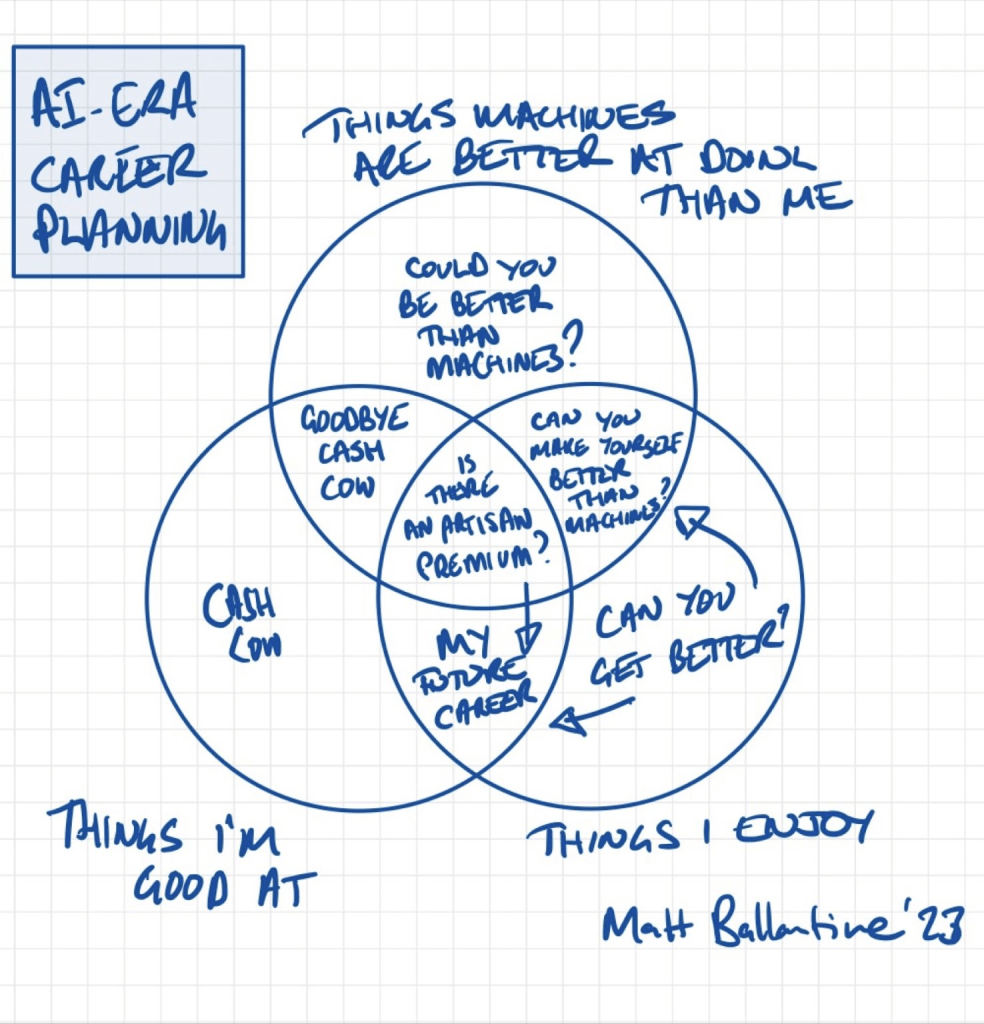

Over the weekend I put a half-thought-through idea onto LinkedIn that has been bouncing around my head for a few days…

I’ve been thinking about how I’ve started to use AI in my work, sometimes consciously, sometimes without necessarily realising, and also about my own personal resistance to the use of automated tools.

It feels like a combination of two dimensions of career planning – what one enjoys and what one is good at – combined with a perspective of what things it is that machines are good (better) at doing. My marketability into the future, I would propose, is based on having a really good handle on the things that I enjoy and I’m good at and are uniquely human.

The hard bit will be to acknowledge the things that I’m good at, I enjoy, but machines can do better than I do. Separation anxiety beckons unless I can come up with a really compelling argument for artisanal services.

The diagram provoked a bit of feedback that maybe the diagram didn’t do enough to explore the “Centaur” idea of how automation technology might work with us to make use work better. It talked about us versus the machines, rather than us with the machines. It’s a fair point (although there’s a bit of me that looks back at a few centuries of industrialisation and wonders if “with” is a bit naively hopeful…)

Anyway, that’s what got me thinking about Hansen, and what I think I was trying to express with the diagram – that adoption of AI technologies will be hampered at a personal level by resistance that will be emotional rather than in any way logical. So if we were to think of generative AI as being a co-working with whom to collaborate, rather than as merely a machine, then does Hansen give us some pointers towards inherent barriers, and in turn how we might overcome them?

Let’s start with the transfer barrier. The explosion of ChatGPT this year has been a fascinating example of the tech hype cycle at work at speed. But the interface really isn’t contextual for anything, which is why we are starting to see GenAI tools being built into other software. I didn’t get it with a chat interface, but simple prompting tools being built into Miro and the Adobe Suite have unlocked a level of utility for me. I’m also learning the language of effective prompting.

How about the search barrier? Well, if you don’t know where to find the tools, you’ll struggle to use them. Given it’s such an emergent field, finding tools that can help in context is a big challenge.

The hoarding barrier is interesting, because in Hansen’s model it’s about the other person being resistant. Are AI tools resistant to helping us? Probably not. However are AI tool manufacturers putting up barriers to their use? Maybe…

OpenAI’s free tools have a bunch of privacy controls that make them unsuitable for anything involving confidential data. Not that that is probably stopping some at the moment. Anything that isn’t free has an inherent barrier to use.

Finally, the “Not Invented Here” barrier is the big block for people at a psychological level. There will be a stack of reasons why people won’t work with new tools: an admission of personal failure or lack of capability; a lack of understanding of how the tool works and whether it gives useful results (a very fair reason!); not wanting to give up things we enjoy; not wanting to make ourselves feel less valuable; a sense that using a tool might somehow be cheating…

Again, these are thoughts in progress. But it does feel like an interesting lens to look through to understand how and why these new technologies might not get the adoption that might at first feel inevitable.

I’ve spent three decades in the world of tech, and technology adoption has been an issue throughout. But one thing is clear for me – I don’t see that this new wave of technologies will be any easier for organisations to adopt. However, we might need different ways of thinking to overcome hurdles that have been adopted before.